|

|

British Foreign Policy 1815-65 |

I am happy that you are using this web site and hope that you found it useful. Unfortunately, the cost of making this material freely available is increasing, so if you have found the site useful and would like to contribute towards its continuation, I would greatly appreciate it. Click the button to go to Paypal and make a donation.

I am grateful to Jim Kelleher, Royal Regiment of Fusiliers, for transcribing this book for inclusion on the web site. The spellings are as they appear in the original book.

After

spending many years abroad, I thought it high time to enter some profession,

and persuaded my father to send me to Mr. Chaplin’s at Gotesburg on the

Rhine, to study for the Army. Among my fellow students were Deering, Dawson-Damer,

Lytton and others. When considered sufficiently prepared to pass the Sandhurst

examination I got my father to enter into communication indirectly with the

Military Secretary, Lord Fitzroy-Somerset, the

result of which was my being directed to see that official in person. He was

subsequently appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Crimean

Expedition. With his one hand my shoulder we entered the room of the Adjutant-General,

Sir George Brown, who later on was

given command of the Light Division in the Crimea. The Military Secretary introduced

me and said that I was desirous of getting a commission in the first regiment

under orders to return home from India. The Adjutant-General demurred, and said,

among reasons, that I had not even passed the usual examination: that I should

have to go through the usual course of drill at the Depôt, etc. However,

the palaver ended satisfactorily, and as the examination was to be held in a

few days, my name was included with that of Jerry Goodlake and others. I passed

out in a very short time, feeling sure that I had good marks. The following

day the Military Secretary was pleased to see me, but much doubted my being

able to proceed with the last draft of the 80th., then under orders, and that

it would take some days for me to get uniform and kit. But was much amused at

my informing him that it was all ready, having obtained it before going to Sandhurst.

Directly the Gazette was published I joined the Depôt, under Colonel Jervis,

at Chatham, and was given quarters by the Quarter-Master. I put my traps there,

and locked the door, then off to the hotel. Next morning, on my return to Barracks,

I found my room door had been forced, the boxes broken open, and the whole of

my belongings, minus a few handkerchiefs, towels, etc., scattered all over the

floor. I had no redress, of course, not having obtained leave to sleep out;

but from what I gathered, the mischief was done by some members of the weaker

sex, who frequently haunted the officer’s quarters.

After

spending many years abroad, I thought it high time to enter some profession,

and persuaded my father to send me to Mr. Chaplin’s at Gotesburg on the

Rhine, to study for the Army. Among my fellow students were Deering, Dawson-Damer,

Lytton and others. When considered sufficiently prepared to pass the Sandhurst

examination I got my father to enter into communication indirectly with the

Military Secretary, Lord Fitzroy-Somerset, the

result of which was my being directed to see that official in person. He was

subsequently appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Crimean

Expedition. With his one hand my shoulder we entered the room of the Adjutant-General,

Sir George Brown, who later on was

given command of the Light Division in the Crimea. The Military Secretary introduced

me and said that I was desirous of getting a commission in the first regiment

under orders to return home from India. The Adjutant-General demurred, and said,

among reasons, that I had not even passed the usual examination: that I should

have to go through the usual course of drill at the Depôt, etc. However,

the palaver ended satisfactorily, and as the examination was to be held in a

few days, my name was included with that of Jerry Goodlake and others. I passed

out in a very short time, feeling sure that I had good marks. The following

day the Military Secretary was pleased to see me, but much doubted my being

able to proceed with the last draft of the 80th., then under orders, and that

it would take some days for me to get uniform and kit. But was much amused at

my informing him that it was all ready, having obtained it before going to Sandhurst.

Directly the Gazette was published I joined the Depôt, under Colonel Jervis,

at Chatham, and was given quarters by the Quarter-Master. I put my traps there,

and locked the door, then off to the hotel. Next morning, on my return to Barracks,

I found my room door had been forced, the boxes broken open, and the whole of

my belongings, minus a few handkerchiefs, towels, etc., scattered all over the

floor. I had no redress, of course, not having obtained leave to sleep out;

but from what I gathered, the mischief was done by some members of the weaker

sex, who frequently haunted the officer’s quarters.

Started with drafts of various regiments under Colonel Wodehouse, 24th.Regiment, for India in the “Bucephalus”; Captain Boxer, commanding the 80th. contingent ( vide ‘ Resumé of Thirty Four Years Service ). Landed at Calcutta, from thence marched to Chinsurah.

One moonlit night, although the sides of the tent had been properly pegged down, just after turning in, I noticed the moon was shining across the tent, and being wide awake, felt certain a loose-wallah was on the prowl; watching carefully, I observed a hand deliberately pushing the flap of the tent on one side, and in a second had seized the thief by his wrist and throwing him over my body onto the floor, but lost my grip as both hands were covered with the cocoa nut oil with which he was smeared, and before I could tackle him again he was out of the tent door, leaving me a knife as a keepsake.

From Chinsurah we had much trouble with the oxen, as many of them broke down, so it became, as usual, necessary to indent the villagers. As they refused absolutely to render any assistance, we were compelled to seize a dozen or more. The natives then, being led by the head men, commenced hammering the guard with bamboo latties; some of them were seriously hurt, but the baggage guard have been quickly reinforced, the disturbance was quelled.

Boxer, being in front of the detachment, soon came back and ordered the ringleaders to be tied to the hackery wheels and get two dozen each. This coming to the knowledge of the Assistant Commissioner, the matter was reported to head quarters, resulting in Boxer getting a wigging; consequently he only acted according to the custom of the country in seizing cattle on Government service, it was rather hard lines, so everyone thought at the time.

At Dinapore in 1851 I contracted, and was in great pain, notwithstanding blisters and poultices. The surgeon of the regiment, R. J. Taylor, afterwards Inspector-General, and Asst. Surgeon M.W.Murphy, having left my room, and being unable to stand it any longer, I rolled off the bed onto the floor, and sent my bearer for the bheestie, who emptied his mussuck of water over me. I was put back to bed, and dozed off for hours without any bad results; it was presumed the schock to the system had polished off the enemy.

In Burmah, 1852, after the taking of Martaban, I contracted inflammation of the liver and spleen. As the application of some eight dozen leeches had not the desired effect, the doctor directed his subordinates to bring down a large commisariat beer-barrel; the top was removed, and the cask, within a few inches of the top, was filled with hot water, and I was put into it, standing, to increase the flow of blood, under the eyes and supervision of the native sentry. Naturally enough he carelessly allowed me gradually to subside, when the subaltern of the day, fortunately for me, going his rounds, noticed the top of my head disappearing, and had me lifted out sharp. The treatment, however, was successful in reducing the inflammation.

Perhaps I may mention here that being a seven-months’ child, and born with a complete caul (still in my possession), the fact of the latter conclusively proved, as sailors have it, that I was not born to be drowned.

Was invalided from Prome with dysentry consequent on a second attack of cholera, and reaching Calcutta on my way home, got a room at the club, centre front first floor, and took a passage in the “Lady Jocelyn”, one of the General S.S.N.Company’s boats. There were only five of these splendid steamers. The French Government, later on, bought three of them for the Crimea. I had filled my cash-box with some 250 rupees to spend at Ceylon, Mauritius, and other places we were to touch at. Two days prior to the steamer starting, on returning to the club in the afternoon, I noticed my kitmugar, Siu-Sahar, a capital servant, who had been with me throughout Burmah, sneaking out the back way, holding in front of him something heavy with both hands in his cummerbund. It struck meas somewhat suspicious, so rushed up to my room, and found the rascal, not being able to burst the lid of the box open from the lock side, had with a cold chisel prized it up from the back and abstracted all my rupees. It did not take me long to catch him up, just as he was entering the China Bazaar, and, as luck would have it, a chokedar was handy and I gave him in charge. The policeman took down the case and told me it would be necessary for me to prosecute at the kutcherry that day week; a likely go. I told him in two days I was off home and could not possibly do so ( considering I had just paid1,200 rupees passage-money) and I left the two together. Expect the division of spoil was somewhat one-sided.

Being one of the two junior Lieutenants in the regiment when it was ordered home, I was in the break, and transferred to the 81st., but managed to get an exchange to the 7th. Royal Fusiliers. This was really tantamount to beginning my service again, as the 7th had the same number of officers as other regiments, but only Captains and First Lieutenants or Ensigns; the only regiment in service having this distinction. On being gazetted, proceeded to Chobham Camp to report myself. Colonel Yea told me that as soon as their time as up at the Camp the regiment was to proceed to Manchester, but that as I had just gone through some real camp work there was no necessity for me to join them, and that I might remain on leave until the Adjutant notified me that the 7th had gone to new quarters, and that he would square matters with the authorities. So I bolted off the Paris to my old diggings, No.13, Rue de la Paix. Spent some weeks there, winding up with the Bal Masque, “Jour de Pâques”- costume, cavalier-temp., Charles I. Had to get the services of a perruquier to dye my hair, who gave me the ingredients and full instructions how to bring it to it’s natural colour again. I had to cross the channel next morning to be in time for muster. Reached Salford Barracks late last night; very dark next morning and an early parade; used the second dressing of the anti-dye with vigour; got to parade a little late, just before the Colonel turned up. By the time he had reached the officer’s, they had edged away from me in a sort of half moon, some of them with hands to their mouths, and I was beginning to wonder at the cause of their merriment, when the Colonel exploded in the vigorous language he was noted for when his dander was up, and ordered me to my room at once, on reaching which I found my hair a lovely green; needless to say, off cam the whiskers in time for me to explain to Speedy, the Adjutant, who came as soon as parade was over, the cause of my trouble. He made it all square with the Colonel, who sent for me and took it in very good part.

From Manchester the regiment went to the Crimea.

At the Alma, when carrying the regimental Colours, and we were busy in a broken line blazing into a Russian column, on their left of the battery facing which the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers, of whom eight were killed outright, I received a bullet, a large conical one, near the right collar bone, which sent me head over heels. After going clean through a Private Barstow’s chest, it passed through my rolled blanket, sash, tunic, brace, shirt, jersey, and lodged just under the skin thoroughly spent. Billy Monk, my Captain, was shot through the heart within a few paces of the Russian column a little to my right front, and in due course I forwarded home to his brother his sword, and shoulder belt which was pierced through and stained with his blood.

The baggage of the regiment was then at Scutari, and there being no prospect of its turning up for many weeks, after the flank march to Balaclava I picked up in a room there a pair of dark green trousers ( my own being so torn ) which had evidently formed part of a Russian officer’s kit, and these, with a thick pea-jacket, the hood of a Turkish grego sewn on to the collar, a Turkish fez, and a pair of loose long boots, lined with sheep skin, completed as a temporary measure my kit until our baggage turned up. Our brigadier, General Coddrington, afterwards Commander-In-Chief, who was always very kind to me, and personally presented me with the Legion of Honour, the day after my return to the Crimea, after a short leave to England, used to be smitten with my costume. Our kits did not turn up from Scutari till the winter was well on.

Good grub was scarce enough, consisting generally of hard biscuits and salt pork, occasionally, but rarely, of mutton or beef, fresh or tinned; but want of water was our special grievance. Coffee beans were issued, but the only fuel obtainable consisted of roots, which the batman collected during the night before the Zouaves and others were about. The little water we could get was from a pool near the spring, just outside our lines, and was barely sufficient for drinking purposes, we scarcely could obtain any for a wash; the men were as badly, or worse, off than the officers. Expect is caused by the 7th. being located on an old Tartar encampment, but frequently during the first part of the winter I had to scrape the vermin off my chest, and once observed a Staff Officer, in the Brigade Camp, close to my tent, occupied in the same exhilarating process. When possible, Ratcliffe, my batman, trudged down to Balaclava, and getting on board one of the ships in the harbour, used to purchase match-boxes by the gross, jam, or anything else he could pick up.

Being off duty from the trenches one day, had a few friends to lunch, having exchanged double the quantity of pork ration for a leg of mutton at the Field Hospital; when the meat was cleared away, Ratcliffe brought in a large rolly-polly jam pudding, and when that disappeared I asked him how he had managed to give us such a treat. His reply was given in a half-suppressed whisper : “Well, sir, seeing no other way, and having an old worsted stocking by me heel-less, I made the pudding and put it in that.” Scarcley necessary to say that my last bottle of Hennessey soon vanished to keep the infernal thing down.

I used often in the trenches to squat on my waterproof rug on the snow, and amuse myself melting the fat of the bacon on to the hard biscuit with the matches my batman had got for me, and this usually formed my only ration.

Bill Hope, 7th., who subsequently won the V.C., had appropriated a large Russian dog in our lines, and little Beauchamp, of ours, was the happy possessor of a small terrier. The Ruski beast one day seized the terrier and had just got half of him in his jaws when I rushed out of the tent, and taking the large dog by his two hind feet, swung him round till he dropped the terrier, and then banged his head on the ground to remind him of his bad behaviour. I heard a day or two after that Hope, who saw the whole thing, and was lying down on his sick bed, had seized his revolver and commenced aiming at me in his fury- the distance between us must have been over 150 yards-but his pistol missed fire. I was glad to hear of it.

On its coming to the turn of my company, at Inkerman, to advance from the Victoria Redoubt to the Lancaster Battery, a distance of about 500 yards, I cautioned the men that as soon as I raised my hand to start, they were to rush across the open at full speed, in order to avoid casualties; and not a man was lost, though the ground was actually being ploughed up with round shot from a Russian field battery on the Guard’s Hill which enfiladed us. On reaching the traverse I noticed our Major, Sir T. Troubridge, with his legs resting on an empty powder case, covered with a cloak. On my enquiring if he were much hurt, he colly replied, “Well, Appleyard, I am sorry to say I have just lost both my feet.” A round shot from what was afterwards called the Black Battery, and which hitherto had been masked, had done the mischief.

We occasionally joined the sailors in a jollification in a good-sized underground crib next to the magazine in the 21 gun (Gordon’s) Battery, they bringing as their share tea and fuel, our being limited to commissariat rum.

On a very cold night in January 1855, with the thermometer nearly 30º below freezing, Waller and I, after going round the sentries in a heavy sleet, entered. In the course of half an hour we were soaked with thaw and steam ( there were some dozen of us in the crib) when a heavy musketry fire was heard in front. We bolted out, and to save time jumped over the parapet to take a short cut across the open, in lieu of going round by the boyaux ; before getting down a third of the way I stuck, my trousers were frozen, and I simply couldn’t move until Bobby broke the ice under my knees; it was a bore being delayed, for the Russians were firing high, and the bullets were whizzing unpleasantly near all round us. However, we managed to get down all right, but not before the row was over.

Poor Cavendish Browne did not hit it off with the Colonel ; so on his coming out from the Depôt at home Yea ordered him to remain at Varna with the heavy regimental baggage and ponies; he, however turned up at the 7th. camp the last day of February 1855, and next day was in orders for trench duty on the 2nd.March. As soon as it got dark that night a party of Greeks, led by a chief, made a raid on our advanced trench in front of Gordon’s Battery; they succeeded in getting to the parapet, and Browne, having already shot in the hand, continued up the trench to where the scrimmage was thickest; there the Greek shot him in the middle of the chest with his pistol; he was struck by two bullets connected together with thick wire, making a hole nearly as gig as a fist. Of curse it killed him at once; but Fisher, my Colour-Sergeant, a knowing old card, in return polished off the Greek (whose object evidently was to fire the magazine- he was near the entrance at the time), and pulling off his right boot, took from it, hanging to the tag, a purse containing thirty Russian sovereigns, remarking to me, “ I wish sir, a few more of them would come”. He was evidently up to the dodge of where they carried their coin.

We had two officers named Jones in the 7th. Royal Fusiliers, nicknamed Alma and Inkerman Jones. The latter, at the taking of the Quarries, went round the Russian side of the parapet and got into a nasty mess by stepping into a small trench of filfth and was often spoken of afterwards as Inkerman Jones, with S.T. before it. Previuos to this, one morning, when in conversation with Rose, one of our Captains, a young gentleman stepped up towards us enquiring for the Adjutant. On Rose asking him what he wanted, he replied “ I am Ensign Jones, just arrived to join the regiment.” Upon which Rose said, “Damn you, you’re the first Ensign to join the Fusiliers.” It certainly was not a very hearty welcome for him.

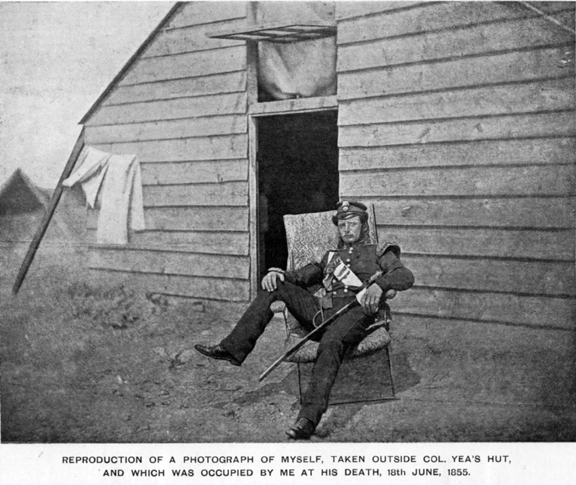

The accumulating hardships of the winter did not prevent the indulgence of taking a rise out of anyone. Vial de Sabligny, great chum of mine in the 2nd. Zouaves, accompanied me to a small entertainment given by the officers of the Chasseurs d’ Orleans, winding up with cafe-cognac. I enquired of my next door neighbour, rather a bombastic swell in his way, whether he had received in his lines the last “Ordre du jour”. Non, monsieur,” he replied ; “mais dites-le-moi, je vous prie.” As he wanted a rise taken out of him, at first I was reticent, but on some of the officers pressing me they drew it out of me pat, and got it : “Soldats Francais, nos braves Alliees prennent les embuscades Russes, te les tiennent.- Canrobert, millbombes.” They were horrified at receiving such a slur in orders, but before long they twigged my chaff, and failing to appreciate it, Vial, dreading some contretemps might put a stop to the general conviviality, begged me to come away. As it happened, whenever our chaps went for the Russian rifle pits they took and held them without fail, whereas this satisfactory result was often the reverse with our gallant allies. Up to the failure of the attack on the day of the first Redan, I occupied a tent, the entrance to which faced the door of Colonel Yea’s hut, but after he was shot, Bobby Waller and I took possession of it. My tent had been dug out two and a half feet, with a ledge a foot broad inside the curtain covered with bits of board from the wine boxes, the pole of the tent resting on an empty barrel, which served as a small table. This enabled me to have plenty of room, and accommodate seven or eight fellows comfortably. Colonel Mundy, 33rd, next lines, was in the habit of bringing me the latest news from home as soon as the mail was in ( having a brother, or connection, at the War Office). He turned up one day, and, sitting on the top step, was reading out to some half-dozen of us the latest news, when Dixon, the Paymaster, approaching from Colonel Yea’s hut, looked over his shoulder and said, “By Jove, Colonel, I wish I had your memory!”. The letter was upside down ; it was only one of his usual yarns. After Inkerman, the operation on Sir Thomas Troubridge, our junior Major ( right leg removed below the knee, and left foot hee turned up), was performed by Drs. Alexander ( afterwards Inspector-General) and Muir, in my tent; also that of Hobson, the Adjutant, after the first attack on the Redan. After Hobson was hit and brought back into the trench, shot in the thigh, I strapped it up as well as I could to stop the bleeding; his trousers were soaked, and his boot full of blood, and he was very weak. On my return to camp in the afternoon, my batman told me that Hobson was as bad as he could be, and sinking, and that he had not recognised anyone; but on entering my tent he looked up, raised his arms, and clasping round the neck said “Ah ! Crockey, old fellow, so glad to see you all right.” Shortly afterwards he expired.

Pitched into my batman for not keeping the tent tidy, and directed his attention to what appeared to be a piece of bacon rind under the step. He replied, “Sir, that’s not pork, it’s a piece of Sit Thomas’s heel.”

In December, 1854, a piquet, unable to find the Adjutant, brought in three Russian prisoners, deserters, to my tent. They looked more like standing bolsters than anything else, and, evidently, in addition to their own clothing, had put over it what they could lay their hands on belonging to their comrades, before sneaking out of Sebastopol. As they looked half starved with cold, I pointed to my recent ration of tallow dips, and on their grinning their delight, gave them half a dozen; they took them by the wicks with thumb and forefinger, drew them across their mouths, and demolished the tallow, leaving the wicks quite clean.

That winter I got both ears frost-bitten, and until about eight years ago still suffered from their peeling round the edges as soon as cold weather set in.

Weak as the regiment was, Colonel Yea remonstrated when the detail was issued for the first assault on the Redan, urging that it was always the first detail to lead, and not strong enough to do the work expected of it; but the orders were out. He, poor fellow, had a presentiment that he would never come out of it this time alive, so the night before, he sent for Dixon, the Paymaster, and another officer, to witness his will.

Not long after our occupation of Colonel Yea’s hut, Waller, sitting on the edge of his bed, was amusing himself cleaning his revolver, I was lying down reading, in the opposite corner, near the door, when off went the revolver accidentally, the bullet whizzing past my head through the planks a couple of feet above it.

During the winter of 1854 we were simply starved, and that too when the real hard work in the trenches was undergone; whereas the French troops were tolerably well looked after. The reverse took place towards the winter of the following year, when all sorts of good things were sent out from home for the British troops, and the French army managed to exist on such indifferent rations as were supplied to them. Consequently, in the early morning they were daily seen frequenting our slaughter camps to pick up anything they could lay hold of, and had been thrown away on one side by the butchers, and then they used to stroll the Light Division camp, from which, at any rate, they filled their empty sacks with bread, biscuits, or anything else that could be spared by our men.

Shortly subsequent to the fall of Sebastopol, Vial and I crossed the Traktir Bridge to the Russian Camp, and at the mess of a Russian regiment of cavalry came across Colonel Barthelesen, Governor of Toula, and then commanding the second cohort. He drove us off in his drosky, and we first visited Fort Constantine. When strolling through an underground passage I came onto the rocks, and noticed some oysters, borrowed a knife from a Russian soldier and thoroughly enjoyed a couple of dozen, to the horror and disgust of the men.

After driving us in his drosky all over that part of the Crimea, the Colonel returned with us at the end of the week; we managed to get across the point of the harbour in time for him to pick up some stout, and champagne at Kamiesh, and drove round that way before returning to the 7th. Lines. Approaching the French camp about dusk, we passed the body of a Jew, murdered and robbed, and within a few minutes were accosted by some half-dozen French soldiers, one of whom said “Halte-la!” and putting the muzzle of his rifle to my chest, accused us of being Russian spies that they were looking for. Considering that this was all rot, the war being over, and fortunately for me I had taken my uniform. I threw open my great coat and showed it. This was enough’ down dropped his rifle, and the Corporal allowed us to drive on. They were simply scamps on the look out for plunder, and no piquet at all, and in all probability had just polished off the poor Jew. Barthelesen was much relieved, and Vial eventually agreed that I must have been right in my suspicion, but that seeing a British officer, and fearing strong measures on their part might lead to trouble, let us go.

Borrowing Colonel Turner’s boat, who had only recently joined the regiment (to do a good turn to which, the Commander-In-Chief had appointed him Governor of Sebastopol), whith some more officers of the 7th, and Mildmay of the Rifles, who had been in the Navy, and taking Ratcliffe and Murphy Carroll (two batmen), started for the Alma by sea, landing at Belbec (see “Resumé of Thirty Four Years Service”). I dawdled about a bit looking after the boat, etc., then went up towards the village, and arriving at a neat little cottage was entering, when a Russian officer accosted me saying that my friends had gone shooting with some of his brother officers, having partaken of lunch with them, and that he just going after them, but hoped I would enter and avail myself of anything that was left. In I went, found the room very dark, with a lamp swinging, and noticed one fellow still at the table, whose face appeared familiar to me: he looked like a parson. Getting more accustomed to the light I stared at him, upon which he jumped up from his chair, begged my pardon, and hoped I would not give him away. He was Ratcliffe, my batman. While the officers were taking their meal he had slipped into one of the bedrooms and changed his clothes for the evening suit, which, having turned up in my kit from Scutari, he had coolly brought in his kit bag, in case anything of this sort turned up, I suppose. He certainly looked like an ideal parson, so I forgave him.

Peace being quite settled, Colonel Mundy, with one or two others, obtained leave to visit Yalta and other pleasant places on the southern coast, and , I remember, took an unusual quantity of baggage with him. On his return journey his mules broke down, and seeing no other way of getting on he exchanged his sorry beasts for some good new ones grazing in a field, notwithstanding the gestural protests of the Tartars in charge. He then proceeded on his journey. The second morning after bagging the mules, he was informed that the greater part of them with his baggage had been looted in the night. However, somehow or another he got back in due course to his own lines, and went straight to Army Head Quarters to report the theft. He was taken to Sir Wm.Codrington’s office at once, and having duly made his complaint, the Chief directed an A.D.C. to take him to an adjacent tent to see if he could recognise his baggage, and much to his surprise, found it intact. He was then taken back to the Chief’s office, and informed by him that his version of the affair did not at all coincide with that of the Cossack officer who had brought it back and recovered his own mules, and that his conduct was most reprehensible. I believe Mundy was confronted with the officer, who was in the next room, and had given the Chief a simple version of the whole affair before Mundy had turned up.

On peace being put in orders I obtained a short leave home and embarked in company with Captain H.R.Hibbert of my regiment, who had been severely wounded in the head at the second Redan.

On board one of the transports there was a curious assortment of passengers, one of whom had the reputation of being the biggest liar in the Navy. Mess being over one evening, yarns were in full swing, and the naval officer was entertaining the others with one of a passenger, who in a gale of wind was washed overboard and swallowed by a fish, which landed him on a sandbank, where he was picked up two days after by a native craft. Roars of laughter, which were quickly, but only momentarily, suppressed by a military corker rising, and , speaking so that all could hear him, saying:” Gentlemen, believe me or not, it’s perfectly true, for I was that man!” Thus capping the Naval officer and scoring one himself. When off at Malta a ship laden with passengers collided with us in the dark, and no sooner had she struck our bow than the first mate and some of her crew jumped on board our steamer and said she was sinking. We were jammed together at the time, and our captain sent on board his second carpenter and a few handy men; there was very little damage done, and they were allowed to accompany her to her destination; but Hibbert, who had been standing near the forecastle at the time of the collision, was very much shaken, so got him to his bunk; but the next day he would persist, against my wishes and the protests of the doctor, on going ashore; the result was that owing to the blazing hot sun he was bowled over, and verging on brain fever. With assistance I got him into the hotel, and put his feet in a bucket of hot water and mustard. As the steamer was due to start about 10.am the following day, I managed to get him taken on board in time. He said, Lennon, his batman, stunk so horribly he could not stand him any longer in the cabin; it was the captain’s, which he had allowed him to occupy; so I had to sleep on the floor with a piece of string tied to his forefinger and the other end to my big toe in case he felt bad in the night. I used to dress his wound early each morning; such a sickening job that I rarely got any breakfast; the suppuration appeared worse towards the end of the voyage, and I was jolly glad when his relatives met us on landing. In the course of a week I went to Birtles, his home to make enquiries as to his condition; Merriman, the Surgeon, was in his bedroom at the time, and turning to Hibbert’s mother, said, “You may thank Captain Appleyard for seeing your son alive.”

I married on 8th December 1855, and went over to Paris. A week had not expired when I received an official letter from the Horse Guards, informing me that an application had been received from the Officer Commanding the 7th Fusiliers to send out to the regiment any officers, then in England, who were available for duty, there being so few at its Head Quarters. I had consequently to return at once. En route out we touched at Malta. The Brigade Major boarded us, and informed me I must stop there, as there was not a single officer of my regiment at the Dept. The ship’s captain, a very good fellow, was close to us, I naturally jibbed, saying that I was proceeding back to the front under special instructions from the Horse Guards; he left the steamer, saying that written orders would reach me as soon as possible after he got back to the Brigade Office. The captain, however, ascertained that the coaling was completed, and weighed anchor and got well away before any shore boat could reach us, I heard nothing more about it.

Joined the Army and Navy Club in 1855

Returned home with the regiment after the Crimea, and the first kit inspection was reminded of an incident which happened in the trenches by a man stepping out (I’m sorry his name has slipped my memory) and saying, “Beg your pardon , sir, but I have brought back from the front something belonging to you,” and taking it out of his knapsack, handed to me the bowl of a cutty-pipe which he had picked up in the trench; I happened to be smoking at the time, and a bullet struck it, breaking it short near the bowl. I kept it for many years with other curios, including the large conical bullet which hit me at the Alma, but, from constantly ashifting quarters, lost them; whether stolen or not I do not know.

After serving for some time at home, the 7th Fusiliers embarked for India in 1857, reaching Karachi too late to take an active part in the Mutiny.

Tom Marten, one of our Captains, had left his wife at home when the regiment started for the East, and not long after it was settled at Meean Meer, she suddenly decided to come out, and her reaching Bombay, Tom secured an empty bungalow in the lines of the officer’s quarters at Meean Meer, and borrowed a few tables, bed, chairs, etc., but seeing the discomfort she would be put to, one of the officer’s wives put her up. The following morning it was found that the centre beam of the bedroom in her bungalow, eaten through by ants, had given way, and the earth roof had come right down on to the charpoy on which, in the ordinary course, she would have slept. It was many a long day before Tom heard the last of his attempt to get rid of his better half.

I returned home in 1858 on leave, to arrange the purchase out of Major Gilley, the junior Major, and on getting a regimental majority exchanged to the 1st. Depot Battalion at Chatham under Colonel Jervis. There happened to be there at the time a very powerful but eccentric officer named Marscak, in the 24th., in our Battalion, who, one day returning from Rochester, heard a disturbance going on at the bar of one of the hotels, and thinking he recognised a voice, entered; seeing some youngsters getting the worst of the row, he soon separated them from their opponents. The fracas came to the knowledge of Major General Eyre, Commanding, who, sending for Marscak, and without listening to any excuse, pitched into him for disgraceful conduct. The following day, in getting out of a train the General slipped, and, and striking is head against the corner of the door, considerably damaged his face.

The first time the General came out to enjoy the air, he went to listen to the band, when Marsack spotted him, and saluting, addressed him thus: “Good morning, General; I see, sir, you have got the blackguard’s mark, now.”

Having had enough of Depot work, I exchanged to the 85th.K.L.I., the 5th February, 1861, and proceeded in command of drafts of various regiments to East London, in South Kaffraria, to take command of the left wing. On my arrival there I found a large percentage of the men in hospital, caused principally by their leading an idle life, loafing about among the natives, especially on Sundays; so sent home for cricket and football gear, and after dinner on Sunday, allowed the men to amuse themselves in healthy exercise; in addition to which, having started a good coffee shop, they lost their inducement of slipping off in the direction of the native quarters for a “Cape smoke,” and worse things.

The Bishop of South Africa heard of my proceedings and strongly remonstrated with General Wynyard, commanding. The Bishop’s official letter was forwarded to me for an explanation, which I sent, shewing the beneficial results which had occurred in the generally improved health of the wing, and that although on my arrival there the hospital was full of sick, and there were then only twelve cases. The General sanctioned what I had done, and the Bishop received a reminder that, as he, the General Commanding the troops, held me responsible for the health and well being of the men under my command, he could not fully approve of the course I had adopted, as it appeared to him to be the only one available for keeping the men fit for duty.

Near Tattenham Corner, at East London, there was a large, deep hole, which at half tide was full, the entrance to which was partially barred by a transverse rock which was nearly covered at high water. Barlee, the Commissariat Officer, Captain Walker, harbour-master, a Scotchman, and I, went down one morning for an early dip. We happened to take headers at the same time. On reaching the surface I called Walker’s attention to something black on top of the water. Looking round he shouted “It’s a shoork, and the sooner we’re oot the better.” We scrambled out sharply enough, getting considerably scratched by the barnacles, but the shark came off second best, for, taking a short cut over the rock at the entrance, he must have cut himself a good deal, the surface of the water near it being covered with blood.

Our bedroom window at East London faced the stable-yard on the ground floor. My wife, being disturbed by a noise one night, woke me up, saying there was a thief about in the yard, she thought. Her side of the bed was about four feet from the window, so I got up quietly, it was a very dark night, and approaching the window, touched something in the angle. In a moment I stretched out both arms and seized the thief, as I thought, by the throat. As it happened, as soon as my dear wife found I was getting out of bed, she slipped out from her side, ensconcing herself in the corner received the grip, and had the mark on her throat for days.

The bar was some distance from the mouth of the Buffalo River at East London, and in one of the gales a barque of about 800 tons, the “Early Morn’,” was wrecked on it. When the gale had subsided, Captain Walker came to me and asked if I would render him assistance in saving her, as he felt sure it was possible, and he would get considerable salvage. I gave into him, and marched the whole wing of the regiment down as the flood-tide was setting in. Barlee provided gear, ropes, etc., from the yard; these were attached to the masts. As the tide set in she was gradually hauled over on her side, and dragged over the bar into the river. Walker gave the men a glass of beer each, rather mean of him as he got over £600 salvage.

When the Head Quarter wing of the 85th. touched at East London to pick up ours for England, I brought onboard two sacks of belladonna and other bulbs; halfway home, choleraic symptoms, or something very similar, broke out among the crew and seized some of our men also; no deaths occurred. When the baggage was landed I missed my two sacks, and it came out that just previous to the cholera scare, when the hold had been opened to get the baggage out for some of the officers, the sailors had spotted my two sacks, and taking their contents to be some special sort of potato, took them to their quarters, cooked a few, and getting nearly poisoned, had pitched them overboard. I should have mentioned that on arrival that on arrival at East London, from Keiskama Hoek, I found it impossible to pick up any sort of furniture, so in my spare time, being fond of carpenter-ing, amused myself in making chairs, tables etc., from empty cases obtained from McDougall’s stores. Prior to embarkation, Assistant-Surgeon Herbert volunteered to sell the lot; so he had handbills posted up in large type, “Bargains! Bargains! Bargains!” and actually realized nearly £100 for me.

Served at home till I got command of the 85th. (vide “Resume of Thirty-Four Years Service”) and we were stationed at Dover and the Curragh Camp, and from the last named embarked for India.

On reaching Meean Meer in 1867, in command of the 85th.K.L.I., General C.T.Chamberlain, in Command of the Division, sent for me, and remarked that as I was probably new to the country he considered it advisable to give me a few hints, which I should find useful in putting into practice; one of which was, that owing to the thieving propensities of the natives, it would be necessary for me to adopt the same system as the Artillery and other regiments, viz., that of “chokedari.” I told him I should take a little time to think it over; the fact was I objected entirely to this system of blackmail and hoped to devise other measures.

A week had not expired, before the whole of the copper dekchies of one of the companies were looted one night. It at once came to the ears of the General, and, of course, it enabled him to say “ I told you so” In the meantime the punkah season had come on, and I secured Luchman, the leading man in the Bazaar, as the regimental contractor, with the proviso in his agreement that he was bound, and held himself responsible for any losses, whatsoever, by theft in the lines of the regiment. Some six weeks had elapsed, when conversing with General Chamberlain, he said he was glad to see his advice had been taken after all, no further losses had been reported to him. I undeceived him at once and told him of the arrangement I had made with Luchman, thus saving the Government some hundreds of rupees during the hot season.

I omitted to mention that, before leaving Karachi for Mean Meer, the following unpleasant event occurred. On landing there, on route for Meean Meer, a case containing some thirty odd silver cups belonging to the officer’s mess was found missing, notwithstanding it was under a special guard with the other mess things, and though every effort was made to recover it, even going so far as to sending divers down the wells, it never turned up. Curiously enough, before a year had run out, if I remember rightly, two of the guard committed suicide, and only about two of it were then left, the rest having died.

From Meean Meer the 85th. proceeded to Dugshai, in the Himalayas, a nice quiet healthy station, and it occurred to me that a considerable saving would accrue to Government, and moreover would be extremely beneficial to the health and well being of the men, if they did their own camp work, as at home, in lieu of their being quite unnecessarily attended to by the camp followers; so mentioned the subject to Lord Napier, Commander-In-Chief, who approving of my suggestion, and considering it worth a trial, directed Colonel Dillon, his Military Secretary, to ascertain if the camp equipage, which had been at the Madras camp of exercise, was available. I started up the Chor Mountain, between Dugshai and Simla, to select a good site on the plateau. Unfortunately a sharp north-easter prevailed at the time, with a hot sun, and after a tedious up-hill tramp, got a bad chill, ending in severe inflammation of the lungs, which in course of thirty hours after arrival home had spread to within an inch and a half of the top each lung, with a temperature of over 105. The doctors, however, managed to check it with blisters, etc., and the inflammation gradually subsided, but in a bad form of pleurisy supervened. I have by me an extract of my case, taken from the hospital records. I was taken ill on the 2nd March, 1872, and on the 10th June, being then convalescent, against the protests of Dr. Richards, took my name off the sick list, on hearing Major Thompson, who had been recalled from leave, arguing with him outside my door about a site for a cholera camp. The doctor objecting to my being disturbed, unknown to my wife I directed the bearer to tell the syce to bring round the tat, and started off to select the ground. Before getting a hundred yards a regular blizzard of snow and hail faced me; I succeeded, however, in choosing a capital site, and felt none the worse for my outing. Sergeant Garvey, hospital sergeant, the first time I went round the hospital, pointing to a shelf in the office, said, ”That’s where I had your coffin, sir, when you were not expected to recover.” I had, of course, been prayed for in church.

Th epidemic of cholera had broken out in the Military Prison. It had once been known to reach Dagshai , and that was when some camp followers, escaping from the plains during Mutiny, had brought it with them. At the expiration of the month in camp, after the last case, the regiment returned to quarters.

The Commander-In-Chief, Lord Napier (accompanied, if I remember rightly, by the Viceroy, who went back after the inspection, to Simla), with Colonel Dillon, his Military Secretary, dined with me. Dillon, on my right ( the dinner, not a la Russe), the Chief sat next my wife at the other end of the table. A few days prior to this I had shot a splendid hare, and, of course, as soon as it was notified to me that they were coming, it was kept for them. When passing the knife along the back of the hare, it burst open and displayed coil after coil of tapeworm. Imagine my horror! Fortunately Lord Napier’s attention was diverted, and so he saw nothing of the contretemps , the kit removing it at once. A week after this inspection by His Excellency ( whose written approval, by the hand of his Military Secretary, is before me, of the manner I had stamped out the epidemic) cholera broke out again in the very same cell where the first victim came from, although thoroughly fumigated, distempered, etc., and it happened to be the very same cell which the Chief, and I believe the Viceroy had entered at the inspection. Of course we had to go into camp again, and, after the usual month, returned to barracks, and no fresh cases occurred.

Bearing in mind how thoroughly the men enjoyed the swimming matches got up for them when stationed in East London, South Africa, and where the first prize was usually carried off by young McLean, son of the Lieutenant -Governor of the Colony, I started regular classes as soon as the regiment got stationed, wherever, jheels of sufficient space were available to commence operations, under the Adjutant and Gymnastics Instructor

Class 1 consisted of men who could swim about 350 yards

Class 2 consisted of men who could swim about 220 Yards

Class 3 consisted on men who could swim about 35 to 40 Yards

I do not happen to have a copy of the yearly returns previous to 1876, but my old Adjutant, now Colonel C. Collett, commanding at Shrewsbury, has given me the following extract from his memorandum book :-

| 1. | Skilled swimmers | 360 |

314 |

354 |

439 |

| 2. | Swimmers | 347 |

340 |

261 |

299 |

| 3. | Non-swimmers | 96 |

147 |

162 |

113 |

| 4. | Not seen | 49 |

36 |

57 |

29 |

| Total strength | 852 |

837 |

834 |

880 |

When Lord Napier was Commander-In-Chief the swimming clause was included in the Regimental State which usually accompanies the Inspection Returns to the War Office, and in the course of time I received an intimation from head quarters to be more careful in the preparation of the regimental return, adverting to the swimmers column; it was certainly very unusual to enter it all, and I suppose mine was the only regiment in India to form those classes. However, in submitting a corrected return, I had the pleasure of stating in the covering letter that since the date of the last inspection some forty more had at least passed into the first class.

The principal events in my career in Afghanistan during the war of 1878-9 are recorded in “Resume of Thirty -Four Years Service”, and I can only recall a couple of others that happened.

At Jellalabad, Bartram, R.E., was one day, with a couple of buckets of water, experimenting on some horses with a strong electric battery he had with him. Some dozen Afghans turned up, and their curiosity was roused to a high pitch; to gratify it, Bartram placed them all in a row, holding each other’s hands; they were all on the grin, when he turned on the battery; in half a minute, leaving their rifles, they scampered all over the place, shouting in their lingo; “The Devil !” thinking I expect the Old Gentleman was at their heels.

Late one afternoon, just as Farwell, Sawyer, and I were about to sit down to dinner, Archibald Forbes turned up, and appeared to have availed himself of the hospitality of his friends en route to our camp. We had a boiled leg of mutton, and Sawyer had brought in from Peshawur a bottle of capers; after helping Forbes, I passed the bottle on to him. During dinner he entertained us with some amusing anecdotes from the Kuram side, occasionally chucking out the capers on to his plate, and he gradually finished the contents of the bottle, apparently being under the impression they were green peas. He was much pleased at our appreciation of his yarns, never dreaming of the real cause of our laughter.

In the spring of 1888, with my wife, I took up a seventy five days’ cruise in S.S.Ceylon, an old P and O boat, and on the 26th March we landed at the Admiralty steps at Sebastopol, 2.30.pm. Drove up the Woronzoff Road, turned off to the left, at the summit, past the old Light Division camp, to the Mill, and which in the old days was used as a powder magazine, the scene of Bill Hope’s exploit, when he got on the top and covered it with wet blankets, as a fire was raging at the time close by. Then on to the sand-bag battery, still in perfect order; the Inkerman memorial column being in very fair condition; thence to Cathcart’s Hill Cemetery, to which all the memorial stones had been removed, and the ground they originally occupied ploughed over, as the Tartars had been in the habit of digging for rings and other relics. At the cemetery in the entrance lodge of which is kept a capital index, I easily found the two old tomb stones of Colonel Lacy Yea, Hobson’s ( the Adjutant of the 7th Fusiliers), Beauchamp’s, FitzClarence’s, and others. Most of the obelisks require repair, more especially that of the Light Division. Thence back to my old tent ground, from which I got a fair start on foot down to the trenches, passing the Victoria Redoubt, and Lancaster, or Hewett’s Battery, where Troubridge lost his feet at Inkerman ( which vividly recalled to my mind the Captain of the Lancaster gun at Inkerman, a splendid fellow being shot through the heart as he was taking aim, close to Hewett); then on to the Quarries and Redan, down the hill, on the other side up to the Malakoff. Small gangs of men with carts are still employed ferreting about and digging for whatever debris they can pick up and carry into Sebastopol. The Redan memorial obelisk, though built of solid blocks of stone, with a wall round two feet high of the same, is in a lamentable state, and unless soon put into thorough repair will probably collapse bodily.

Owing to the heavy winter of 1887-8, the country from the Severnaia to the Alma was almost impracticable for travelling, more especially as we could only spare two whole days in the Crimea; so on the 27th. we crossed early to the north side, visited the Russian graveyard, which they say cost £200,000; it certainly contains a magnificent mausoleum, and no one is allowed to be interred within its precincts unconnected with the defence of Sebastopol. In the enclosure are six English guns ( taken from the Turks at Navarino). From thence drove round the head of the harbour to Inkerman Caves and St. Clement’s Monastery. The old doorway and wall on the face of the cliff, opposite our old right flank, are riddled with round shot. Thence on to the Sandbag Battery, passing the aqueduct, where we quenched our thirst pretty freely, bivouacking on the flank march from the Alma to Balaclava, and now dry, to the ground of the Light Cavalry charge, and that of the Heavy. The obelisk erected to commemorate the event is in very fair order. Balaclava is now becoming a favourite watering place, and is much improved since the old times.

We returned by the old French, kin capital order, past the site of good old Mother Seacole’s hut (whose hostelry never appeared short of grub of some sort, in the old days), breaking into the post road near Lord Raglan’s old house ( which has just been sold with 60 aces of ground for £900); then past Pelissiere’s. It is quite easy to recognise the formation of the several camps by the scattered piles of broken bottles glistening in the sun near the officers’ messes and hospital tents. Spent the remainder of time in Sebastopol itself. Docks all in working order. No fortifications have been erected to replace the old stone ones on the south side, but in lieu thereof there are several earthworks armed with 25 and 38 ton Krupp guns, some 50’s also, but not yet in position. Nearly half the town has been re-built, the remainder, it is expected, will be completed in a couple of years. There are two clubs, one for naval and military officers of the garrison, and the Yacht Club, near the Admiralty, on the site of old Fort Nicolas. The former is a very fine building, given complete by the Emperor, lighted entirely by electricity, and in addition to the usual rooms has a splendid ball room, with ladies anti-room and boudoir, and furnished with the fittings of the yacht “ Livadia,” which the Czar does not use now. The annual subscription for members is about 27 shillings and no entrance fee.

Left 4.p.m. 28th. March. The officers at the club were most hospitable, and entertained us royally. The Port Admiral told me he was a Lieutenant in charge of the battery at the N.W. angle of the Redan during the seige, and every morning at one time tried to bowl over an officer who rode a grey horse; but much to his disgust he invariably turned up again the following day. This was evidently our Brigadier, old Codrington. He also informed me that the whole of the alterations at Sebastopol should be completed after a couple of years, and then it would be converted into an Imperial port, and all passenger and merchant vessels would have to content themselves with finding shelter in Strelitza Bay.

The following are extracts from old Crimean friends on the subject.

Man. C. Milligan, 39th., was ADC to Lord W.Paulet our Divisional General, and General Sir Arthur Herbert, K.C.B, formerly a Major of the 23rd. Royal Welsh Fusiliers, and afterwards Quarter-Master-General at the Horse Guards.

Caldwell Hall, Burton-on-Trent

10/12/198

My dear Appleyard,----

Many thanks for sending me a copy of your very interesting paper on the battlefields of the Crimea. It brings it all back to one’s memory very vividly, and quite helps to reconcile me to not having gone there this year in the “Lusitanea” as I very nearly did. I am glad to hear from a friend who was there this year that the road you called the old French road is in such good repair, as I was an assistant engineer on the section from Balaclava to the Coll. I always said it would last for ever, the foundation was so good. I am trying to get a plan and key to the Cemetery, but it is beyond the ken of our Intelligence Department. I believe in a German Bureau they would have put their hands on one affecting their own Army at once.

Again thanking you for your paper, which I shall place with my Crimean records,

Believe me, sincerely yours

(Signed) C. Milligan

Hotel des Alps

Territet, Lac de Geneve

3rd June 1888

My dear Appleyard,----

You will have thought me very remiss in not having ere this acknowledged your graphic description of the old ground on which we spent such a miserable winter; but I have only this morning read your letter, as we have been constantly on the move lately, and my letters were not forwarded till I wrote for them. What an interesting trip you must have had ! I would gladly like to do ditto, but my wife is such a bad sailor marine excursions are out of the question, etc., etc.,

I hope when we return to our house in London in the Autumn, you will, when passing, look in and give me a few viva voce stories of your trip.

With many thanks for having written,

Believe me, yours sincerely,

( Signed) Arthur Herbert

LIST OF CASUALTIES AMONG THE OFFICERS OF THE ROYAL FUSILIERS FROM JULY 1854, TO THE CAPTURE OF SEBASTOPOL

| Rank and Name | Killed | Died |

| Capt. Wallace | At Varna, in July, 1854, from the effects of a fall from his horse | |

| Capt. The Hon. W/Monk | Alma | |

| Capt. The Hon.C.L.Hare | On Board the “Andes” 22nd September, 1854 of Wounds, received at the Alma | |

| Capt. The Hon. C. Browne | In the trenches before Sebastopol 2nd March 1855 | |

| Lieut. R.Molesworth | At Malta, October 6th.1854, of brain fever | |

| Colonel W.L.Yea | First Redan | |

| Lieut. And Adjt. St.C.Hobson | First Redan | |

| Lieut. The Hon. E.FitzClarence | In Camp, from loss of right leg, First Redan | |

| Lieut. O. Colt | Second Redan Attack | |

| Lieut. L.L.W. Wright | Second Redan Attack | |

| Lieut.-Col. M Mills | At Portsmouth August 1855, of wounds received at the taking of the Quarries. | |

| Lieut. G. Beauchamp | Before Sebastopol, October 4th. 1855, Bronchitis | |

| Qr.-Mastr.. Hogan | Cholera, at Monastir | |

| Asst. Surgeon Langham | Dysentry, at Scutari |

LIST OF OFFICERS OF THE ROYAL FUSILIERS WOUNDED FROM THE LANDING IN THE CRIMEA TO THE TAKING OF SEBASTOPOL

| Capt. C.Watson | Severely | Foot | Alma |

| Lieut. R. Hibbert | Slightly | Feet | Alma |

| Capt. R. Hibbert | Very Severely | Three places-head | Second Redan |

| Lieut. F E Appleyard | Slightly | Shoulder | Alma - Carrying the Colours |

| Capt. F E Appleyard | Slightly | Stomach | First Redan |

| Capt. F E Appleyard | Slightly | Leg | Taking the Quarries. The wound broke out again and prevented him from taking part in the Second Redan. |

| Lieut. G.W.Carpenter

|

Severely | Thigh | Alma |

| Lieut. P.G.Coney | Severely | Left arm broken | Alma |

| Lieut. Dudley Persse | Severely | Throat | Alma |

| Capt. W. FitzGerald | Severely | Both Legs | Alma |

| Lieut. The Hon. H. Crofton | Slightly | Ankle | Alma |

| Lieut. H.M.Jones | Severely | Jaw Broken | Alma |

| Lieut. H M Jones | Severely | Left Shoulder | Taking of Quarries |

| Lieut. H Jones | Dangerously | Chest | Second Redan |

| Maj. Sir T. Troubridge | Dangerously | Lost both feet | Inkerman |

| Capt R Shipley | Severely | Hip | Inkerman |

| Lieut. G Butler | Severely | Leg | Inkerman |

| Capt. E Rose

|

Slightly | Chest | Inkerman |

| Ens. L.J.F. Jones | Slightly | Right hip, right arm | Inkerman |

| Ens. L.J.F. Jones | Slightly | Left hip | Trenches March 27th 1855 |

| Ens. L.J.F. Jones | Slightly | Head | Trenches 5th April 1855 |

| Ens. L.J.F. Jones | Slightly | Leg, left hand | Taking of Quarries |

| Ens. L.J.F. Jones | Very Severely | Right foot broken, knee, back | First Redan |

| Lieut. J McHenry | Severely | Left arm | trenches 22 March 1855 |

| Capt W W Turner | Slightly | Shoulder | Taking of Quarries |

| Major W W Turner | Slightly | Head | Second Redan |

| Lieut G H Waller | Slightly | Head | Taking the Quarries |

| Lieut G H Waller | Slightly | Arm | First Redan |

| Major A Pack | Severely | Left Leg | First Redan |

| Lieut. Lord R Browne | Severely | Right Hip | First Redan |

| Lieut D Robinson | Slightly | Eye | First Redan |

| Lieut C Malan | Very Severely | Both thighs, left shoulder, right hip | 1st. Redan - Since Dead |

| Lieut. Col. J Heyland | Severely | Ankle | 2nd Redan |

| Capt. F J Hickie | Severely | Head | 2nd Redan |

| Lieut. St. Clair Hobson | Slightly | Thigh | Alma |

| ALMA | 10 | TRENCHES | 3 | FIRST ATTACK ON REDAN | 8 |

| INKERMAN | 5 | QUARRIES | 5 | SECOND ATTACK ON REDAN | 5 |

| TOTAL | 36 |

| Meet the web creator | These materials may be freely used for

non-commercial purposes in accordance with applicable statutory allowances

and distribution to students. |

Last modified

12 January, 2016

|