|

The Peel Web |

I am happy that you are using this web site and hope that you found it useful. Unfortunately, the cost of making this material freely available is increasing, so if you have found the site useful and would like to contribute towards its continuation, I would greatly appreciate it. Click the button to go to Paypal and make a donation.

The first incidence of cholera in England occurred in Sunderland in October 1831 when a ship, carrying sailors who had the disease, docked at the port. The ship was allowed to dock because the port authorities objected to, and therefore ignored, instructions from the government to quarantine all ships coming from the Baltic states. From Sunderland, the disease made its way northwards into Scotland and southwards toward London. Before it had run its course the disease had claimed some 52,000 lives.

From its point of origin in Bengal it took five years to cross Europe, so that by the time it reached Sunderland, British doctors were well aware of what cholera did. No-one knew how to prevent the development or spread of cholera because the discovery of germs — which are the cause of cholera — did not happen until 1864. Even worse, no doctors knew how to treat cholera patients. There were two medical theories related to the spread of disease in the 1830s. One was that disease was transmitted by touch (contagion) so doctors wanted to isolate patients. The other theory was the miasmic theory, which taught that disease was spead by bad smells, bad air or 'poisonous miasma'. In the later 1820s, doctors had connected dirt with disease but they believed that disease was carried by the smell; Consequently, orders were issued for the lime-washing of houses to try to clean them up. Barrels of tar and vinegar were burned in the streets to try to remove the bad smells. None of these efforts had any effect whatsoever. The symptoms were vomiting, diarrhoea and sweating. Death could — and did — occur within hours of the first symptoms showing.

Despite the panic and the official investigations, when the disease reappeared in 1848 past issues had not been resolved and another deadly epidemic ensued.

The Cholera Morbus was first noticed among British troops in India and was first described near Jessore in 1817. By 1823 it had spread to Russia and vivid accounts appeared in the press of the effects of cholera in St. Petersburg. This first hand knowledge of the disease, and reports of the mortality it could cause in large cities, led the Privy Council to put all ships for Russia arriving in England under quarantine in January 1831. By 1831 cholera had arrived in Hamburg, and the first case in England was reported in October 1831 in Sunderland. The first case in East London was on 12 February, 1832. For all the fear attached to this new disease, only about 800 persons died of cholera in the East End. In 1832 more people died of tuberculosis than from cholera, and a child born into a labouring family in Bethnal Green had a life expectancy of only 16 years. However, cholera evoked a response in social terms, and a contribution to the development of public health, of far more significance that its effect on mortality at the time.

Cholera Morbus is what is now known simply as cholera; in the 1830s the terms Asiatic, spasmodic, malignant, contagious and blue were also used to describe this new disease which was generally thought to be a more serious form of the contagious cholera already well known. It was confused with 'common' or 'English' cholera — dysentery and food poisoning frequent in this country during the summer months.

It is now known that the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, if drunk in water contaminated with infected sewage, causes a mild fever that usually gets better within a week. However, a poison produced by the bacterium stimulates a profuse diarrhoea that may prove fatal if the vast quantities of water and salts lost are not replaced. Cholera is not a serious disease if treated correctly, but doctors in the 1830s generally tried to restrict fluid intake, to prescribe emetics and purgatives, and even to bleed their patients, trying to 'equalize the circulation'.

The Privy Council had set up a Central Board of Health in 1805, after concerns about yellow fever arriving in Britain. This Central Board was reconstituted and met daily from June 1831 to May 1832. It issued circulars and gave advice to parochial Vestry Committees, who were responsible for the precautionary measures taken within their own parishes.

The progress of the illness in a cholera victim was a frightening spectacle: two or three died of diarrhoea which increased in intensity and became accompanied by painful retching; other symptoms included thirst and dehydration; sever pain in the limbs, stomach, and abdominal muscles; sometimes there was a change skin hue to a sort of bluish-grey. The disease was unlike anything then known. One doctor recalled:

Our other plagues were home-bred, and part of ourselves, as it were; we had a habit of looking at them with a fatal indifference, indeed, inasmuch as it led us to believe that they could be effectually subdued. But the cholera was something outlandish, unknown, monstrous; its tremendous ravages, so long foreseen and feared, so little to be explained, its insidious march over whole continents, its apparent defiance of all the known and conventional precautions against the spread of epidemic disease, invested it with a mystery and a terror which thoroughly took hold of the public mind, and seemed to recall the memory of the great epidemics of the middle ages.

In the summer of 1831, after news had reached England that a cholera epidemic had arrived in the Baltic ports, Charles Greville said in his Memoirs [chapter 15]

The last few days I have been completely taken up with quarantine, and taking means to prevent the cholera coming here. That disease made great ravages in Russia last year, and in the winter the attention of Government was called to it, and the question was raised whether we should have to purify goods coming here in case it broke out again, and if so how it was to be done. Government was thinking of Reform and other matters, and would not bestow much attention upon this subject, and accordingly neither regulations nor preparations were made. All that was done was to commission a Dr. Walker, a physician residing at St. Petersburg, to go to Moscow and elsewhere and make enquiries into the nature and progress of the disease, and report the result of his investigation to us. … we took no further measures until intelligence arrived that it had reached Riga, at which place 700 or 800 sail of English vessels, loaded principally with hemp and flax, were waiting to come to this country. … The Consuls and Ministers abroad had been for some time supplying us with such information as they could obtain, so that we were in possession of a great deal of documentary evidence regarding the nature, character, and progress of the disease. The first thing we did was to issue two successive Orders in Council placing all vessels coming from the Baltic in quarantine …

As the disease spread west to Hamburg, all ships from Baltic ports were put under quarantine. Those arriving in London had to spend ten days in Standgate Creek, near Deptford, before a doctor gave the ship a clean bill of health, 'the last three days of this period to be bona fide employed under proper supervision in opening hatches .... and ventilating the spaces between decks by Windsails, and opening, airing and washing the Sailors' clothes and bedding.'

Vessels from Sunderland were put in quarantine by the end of November 1831, soon after the cholera had arrived there. The measures were not completely effective because the first cases in London occurred on the river, mostly on colliers from the Tyne. During December and January there were a large number of cases of suspected cholera in London, and the prospect of an epidemic received a lot of attention. John James, a ship scraper two days off the Elizabeth from Sunderland, was the first death ashore, in Rotherhithe on 11 February. North of the river the first case was that of Sarah Ferguson, taken ill on the afternoon of Sunday 12 February. She was quickly moved from White's Rents, Nightingale Lane, to Limehouse Workhouse, where she died eight hours later. Her extremities turned a blue colour shortly before death, confirming this was the 'Asiatic' or 'blue' cholera. Another woman, Mary Shea, and her daughter Caroline, were taken ill at the same time and both died. All three were buried as soon as possible in deep graves in the corner of the churchyard.

A Board of Health was set up in Sunderland in June and William Reid Clanny, the senior physician of the Sunderland Infirmary, was invited to head the Board's medical department. Clanny immediately called a meeting of the town's medical personnel. The other key figure who was present, was James Butler Kell, an army doctor stationed in the town who was the only one with actual experience of the disease, having suppressed an outbreak of cholera in Mauritius by implementing a strict quarantine.

One of the first cholera victims in Great Britain: a girl who died of cholera in Sunderland in November 1831.

One of the first cholera victims in Great Britain: a girl who died of cholera in Sunderland in November 1831.

By September Kell was starting to hear of suspected cases of cholera in Sunderland. He reported these to the Board but had no real evidence and so attracted little attention. The Board did, however, draw up a Code of Sanitation, a measure which was dismissed as unnecessary meddling by the townfolk. As in most British towns, standards of sanitation in Sunderland were low as there was no regulation of housing, water supply or sewage.

Clanny realised, with hindsight, that one of his patients, Robert Joyce of Cumberland Street, must have been suffering from cholera. Diagnosis was difficult because there was confusion over the symptoms of the disease. Various typhus-like illnesses had long been described in Britain as 'cholera' and Clanny did not realise that cholera, arriving for the first time in Britain, was a completely different disease; nor did he realise how the contagion spread.

It is probable that the first cholera victim was a river pilot called Robert Henry but his death went unreported. On 17 October a 12-year old girl called Isabella Hazard, who lived near the quayside suddenly fell ill and died within 24 hours. On 23 October a 60-year old keelman called William Sproat became the first 'official' victim is . He lived very near to where Isabella Hazard had lived. Sproat's wife sent for Dr Kell, who confirmed that Sproat had cholera. Kell called in Dr Clanny and they managed to keep Sproat alive for three days. His son and granddaughter were also struck down, as was the nurse who handled Sproat's body. Four days later the authorities had still not been officially notified so Kell did it himself, prompting Clanny to act.

On 1 November. Clanny called a meeting of the Board's medical department; the doctors and surgeons finally accepted that cholera has struck. Dr Daun, a medical officer from London was sent to initiate a fifteen-day quarantine enforced by a frigate in the harbour. This was supposed to prevent ships from arriving or leaving the harbour. The Privy Council sent Lieutenant-Colonel Michael Creagh to see that the quarantine was enforced. The resulting decline in trade caused a great deal of resentment among businessmen. An 'anti-cholera party' was formed of local businessmen and leading citizens to discredit the cholera talk.

On 12 November an extraordinary meeting of the Board was called at the Exchange Buildings. Influenced by the business community, the town's doctors withdrew their former opinion that Indian cholera was affecting Sunderland. Kell and Clanny refused to attend but the meeting was reported nationally and caused a scandal. Other towns started to boycott Sunderland. Kell responded by putting his own barracks, the home of the 82nd regiment which was right in the heart of the Cholera district, under strict quarantine and not a single man fell ill. However, in the rest of the town, the epidemic proceeded rapidly.

On 16 November, the Bishop of Durham called for a day of fasting and prayer while the doctors start to withdraw their change of opinion, as the death toll mounted. Fear of post mortems and body snatching meant that the sick refused to go to the cholera hospital but Clanny and Kell orchestrated a great clean up campaign, providing free quicklime and men to sweep the streets twice a day. Blankets were handed out to the poor. Doctors from all over the world arrived as 'cholera tourists', to marvel at the clean up and to stare at the sick.

By late December the disease appeared to have been contained but it had already reached Gateshead, where it suddenly broke out at Chistmas time. There were many fatal cases. From Gateshead, cholera reached Newcastle and then further along the coast and inland.

On 9 January 1832 the Board of Health declared that Sunderland was free of cholera. There had been 215 reported deaths. Unknown to the board, a young doctor called John Snow was working single handed with the epidemic in Killingworth Colliery, a Tyneside coal mining village. His experience led him to make an important discovery which he used in London during the cholera epidemic of 1848.

On 26 May, cholera arrived in Leeds:—

On 26 May the first case of pure cholera occurred in Blue Bell Fold, a small, dirty cul-de-sac containing about twenty houses inhabited by poor families. Blue Bell Fold lies on the north side of the river between it and an offensive streamlet which conveys the refuse water from numerous mills and dyehouses. The first case occurred in a child two years of age which having been in perfect health on the preceding day became suddenly ill on the morning of the 26th and died at 5 p.m. on the same day. If the Board will refer to the map which accompanies this report they will at once see how the disease was worst in those parts of the town where there is often an entire want of sewage, drainage and paving. Dr Baker, District Surgeon, Report to the Members of the Leeds Board of Health, January 1833. |

By 22 July, cases were being reported in Manchester: —

A more unhealthy spot than this (Allen's) court it would be difficult to discover, and the physical depression consequent on living in such a situation may be inferred from what ensued on the introduction of cholera here. A matchseller, living in the first story of one of these houses, was seized with cholera, on Sunday, July 22nd; he died on Wednesday, July 25th; and owing to the wilful negligence of his friends, and because the Board of Health had no intimation of the occurrence, he was not buried until Friday afternoon, July 27th. On that day, five other cases of cholera occurred amongst the inhabitants of the court. On the 28th, seven, and on the 29th, two. The cases were nearly all fatal. Those affected with cholera were on the 28th and 29th removed to the Hospital, the dead were buried, and on the 29th the majority of the inhabitants were taken to a house of reception, and the rest, with one exception, dispersed into the town, until their houses had been thoroughly fumigated, ventilated, whitewashed, and cleansed; notwithstanding which dispersion, other cases occurred amongst those who had left the court. Sir James Kay-Shuttleworth The Moral and Physical Condition of the Working Classes of Manchester in 1832 |

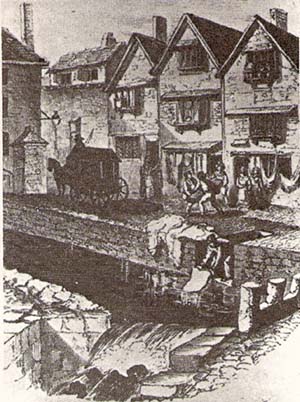

Exeter in 1832: the body of a cholera victim is carried away; the bed clothes are being washed in the stream, which is the local water supply for the other inhabitants.

Exeter in 1832: the body of a cholera victim is carried away; the bed clothes are being washed in the stream, which is the local water supply for the other inhabitants.

In the summer of 1832 the Anatomy Act was passed; it said that bodies unclaimed at hospitals or workhouses may be used for anatomical dissection. By that time, cholera has reached Liverpool and fears grew that the sick will be whisked off by the 'burkers' (named after Burke and Hare). This led to a succession of 'Cholera Riots' in the town.

In January 1832, when the first cholera case was reported in London's Limehouse district, there was considerable panic immediately, in the whole of London. Almost any mild bowel problem was thought to be cholera and even twelve horses that died of a 'rapid febrile disease' at Taylor's brewery, Limehouse, were rumoured to be victims of the epidemic. As the disease carried off relatively few people in its early stages, this alarm subsided a little, although East London found itself almost in quarantine. The chairman of a meeting of the Mechanics Institute in Limehouse failed to attend for fear of catching the disease, and a member wrote to him that 'gentlemen at the west end of the town are mightily afraid of the cholera; he hoped they would get their share of it.' The Marquis of Stafford would not permit his staff to venture east of Charing Cross, and had his post thrown into his house from the street.

The Central Board had been supervising activity in the parishes for three months bye the time cholera did arrive in London in February 1832. The Vestry Committees had been asked to form local boards of health on 20 October but there was little initial response. Following the news of the arrival of cholera in Sunderland on 5 November, there was a flurry of activity. With the encouragement of the two Central Board Inspectors for East London all the parishes formed boards, apart from Holy Trinity Minories where the Vestry asked the Clerk and Wardens of the Liberty to use their 'discretion' as necessary 'on the spur of the moment'.

Most of the boards seem to have examined the cleanliness of their parishes, and cleared 'nuisances' off the streets. 'Nuisance' was a euphemism for human and animal effluent, rubbish, dead animals, household waste, rotting vegetables and all other noxious substances which were to be found inthe streets. Initially there were no powers for statutory cleansing of private property, but Poplar Board of Health kept a free supply of brushes, buckets and unslaked lime at the Town Hall for the poorer inhabitants to borrow. Surviving accounts of the living conditions paint a picture of overflowing cesspits, pigs in the backyard, and inadequate drainage and water supply. In Spitalfields

the low houses are all huddled together in close and dark lanes and alleys, presenting at first sight an appearance of non-habitation, so dilapidated are the doors and windows:— in every room of the houses, whole families, parents, children and aged grandfathers swarm together.

Cross Street, Poplar, was not in a particularly dirty area but the report of the Board of Health says it

wants cleaning, especially a pool of stagnant water at the top of Mary Street which has no protection against children falling in, one case having occurred, where the child would have been smothered had it not been for the timely assistance of its mother and a boy. NB the pigs which wander about these parts turning up the earth and heaping up ashes etc., contribute to the nuisance.

Drainage in East London was very poor, as indeed it was over the whole of London. The Commissioners of Sewers, set up by Henry VIII, collected a rate and were meant to maintain the sewers in their area. However, many of the sewers were open ditches, and those which did run underground had not always been properly surveyed, so that the course became blocked up. The worst drain was the 'Black Ditch', an open sewer running from the parish of Christ Church Spitalfields and emptying into Limehouse Dock. The Tower Hamlets Commissioners of Sewers had made an attempt to drain it by diverting the flow, but this had made the stream stagnant and more offensive. The Act for the Prevention of the Cholera Morbus came into force in February 1832 and allowed boards to perform some compulsory cleansing of houses for the first time, but was passed too late to have much effect on the epidemic already in progress.

Water was supplied to London by private companies, the New River Company and the East London Water Company serving respectively the inland and riverside parts of East London. The East London Water Company took its water directly from the River Lea north of Bow, and despite having recently replaced the wooden mains piping, the mortality from cholera was very high in the area it served. Only about a third of houses were supplied directly, most people relying on pumps in the street.

Ordering the provision of cholera hospitals was the other major measure the Central Board took, and all the local parishes made some arrangements, except the Hamlets of Mile End Old and New Towns, Bromley and Spitalfields. The London Hospital, in common with other voluntary hospitals in London, affirmed its general rule not to admit anyone with infectious diseases. All new patients were examined in the waiting hall before admission, to check for any symptoms of cholera. A ward for cholera victims was set up first in the Library, and then in the attic above Harrison Ward, but only for patients already in the hospital who happened to catch the disease.

Limehouse, Wapping, Shadwell, Whitechapel and Bethnal Green converted parts of their already crowded workhouses into wards, but the Central Board favoured the use of detached houses, where the risk of contagion was less. The only good surviving description of one of these hospitals is of the one in St. George's in the East. It was in two adjoining houses on Vinegar Lane, with a back entrance from Sun Tavern Fields. The Board of Health:

had provided sixteen beds, with entirely new bedding, nurses, a surgeon to attend on the patients, and pipe conductors of steam, to convey heat to the afflicted persons and beds. [They] had also provided a litter, made of wicker, and which could be covered in at pleasure, for the easy removal of persons from their houses; and immediately under the patients a portable steam apparatus, which would act to keep the patient warm during his conveyance through the open air. The hospital ... was situated in the most airy part of the parish.

Although there had been a number of Central Board circulars on hospitals, only Poplar had actually set one up by the time cholera had reached London, and the other parishes made more or less hurried attempts to rent houses or convert parts of their already overcrowded workhouses in early February.

The parishes of East London were certainly not well prepared for the first cases of cholera. The local boards were free to do largely as they wanted, and were not guaranteed support from the Vestry Committees; the Limehouse and Ratcliffe boards received little co-operation or money from their parishes. A long-standing conflict between the Vestry and local Magistrates of St. Dunstan's, Stepney, resulted in the formation of a 'voluntary' board. This spoke out against excessive expenditure, asked for a public subscription, and proclaimed 'the poor want bread not warm baths and physic'.

The attitude of each board was strictly parochial, and anyone who was not the proven responsibility of a parish would receive no aid, nor even burial. Thus when the captain of a vessel moored off Hermitage Pier, Wapping, was brought ashore in a state of collapse, and it could not be decided which parish his ship was moored nearest, he was left lying alone on the wharf.

As with most government bodies at this time, the Central Board had very few actual powers, and the preventative measures it recommended were inadequate to control the disease. The Central Board soon took special precautions on the river, using the frigate HMS Dover as a cholera hospital. The Admiralty had offered another frigate HMS Grampus as a hospital as early as November 1831 but the Central Board did not take up the offer until cholera was actually in London. The Dover was first moored near Limehouse, then off Hermitage Pier, Wapping, from the end of May. On board were a lieutenant, eight crew, medical staff and nurses; female nurses had to be taken on board from Greenwich after the original male crew refused to attend the sick. A boat rowed along the river front every day, and collected any new patients.

The doctor in charge, Surgeon Inlay, treated 64 patients in the first two months of the epidemic, mostly off colliers - the Formosa, the Blessing, the Blossom, the Maxwell and others lying off Hermitage Wharf and Stone Stairs. It could not have been an easy job, as Inlay and his three nurses all got diarrhoea themselves.

There was always trouble over where the bodies could be buried. Poplar was closest to where the Dover was first moored, but together with Limehouse, maintained that the bodies should be buried on open ground south of the river, by the convicts' cemetery at Woolwich. This Inlay was forced to do, after the first bodies had spent a week on the ship, despite orders sent down to Poplar from the Central Board.

The cholera epidemic of 1848 visited the same places as the first outbreak and found the same state of unpreparedness. Treatments and preventative measures all failed, and evidence suggests that the death rate was higher. But there was a change in the dominant public mood which reflected greater changes in attitudes to health, government, religion and science. After the epidemic there was none of the sudden loss of interest in cholera which had taken place in 1832. The Edinburgh Review and the Christian Remembrancer both reviewed the government reports on the epidemic, whilst the medical journals showed none of the 'boredom' they had expressed in 1832.

There were several reasons for the change. During 1847, thousands of starving Irish people had fled from potato blight and brought typhus to the large cities of Britain. Those who had seen 'famine fever' in the crowded centers of Glasgow, Manchester and Leeds could not view cholera as an unprecedented horror. The public health reports of the 1840s were slow to produce practical results in terms of government action, but through the many articles, pamphlets and public meetings they provoked, these reports gave public and government opinion a thorough education in science-based, especially miasma-based, attitudes to public health problems.

Although they had little more to offer in 1849, the medical and scientific community were much more assured than they had been in 1832. Many doctors had seen cholera in 1832 and there were fewer disputes over the identity of the disease. The government was better informed. It had its own network of local agents, the local Registrars of Births, Deaths and Marriages, who were able to check reports by simple reference to death certificates. In addition, the General Board of Health employed two medical inspectors of their own, Drs Sutherland and Grainger, who were also able to check local reports and conditions. The new railway network meant they were able to do this with a speed impossible in 1832. The regular publication of weekly tables by the Registrar-General replaced the rumours which abounded during the first epidemic. The profession itself was better organized for carrying out and discussing research. There was a network of journals which exchanged information across Europe. Most of the provincial hospitals had medical schools attached to them, and in the 1830s many towns had formed provincial medical societies which were a base for research. In addition the medical and scientific resources of London were greater, and included the increasing government interest in statistics.

Miasmatic thinking dominated official medical and government statements. When the Royal College of Physicians asked for the views of members they had 84 replies: 32 rejected contagion and only 7 gave unqualified support. The others were uncertain or held that both modes of diffusion could operate under different conditions. The recently created General Board of Health, like its secretary Edwin Chadwick, was aggressively miasmatic. The ready acceptance of this theory was helped not only by the public health campaigns of the 1840s but also by the methodology of an increasing number of statistical studies of disease. These depended on figures gathered by geographical area. Hence attention was directed to localized influences which in turn, with the help of the nauseating smell of many of these areas, was related to miasma.

The disease returned three times, in the pandemics of the late 1840s, mid 50s and mid 60s, but never again reached epidemic proportions in Britain.

The information contained in this page has been synthesised from a number of sources. Among the internet materials is information from these sites:

http://www.mernick.org.uk/thhol/1832chol.html

http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/longview/longview_20030415.shtml

http://www.medicinenet.com/cholera/article.htm

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs107/en/index.html

| Meet the web creator | These materials may be freely used for

non-commercial purposes in accordance with applicable statutory allowances

and distribution to students. |

Last modified

27 June, 2020

|